The Seat at the Centre

1st February, 2026

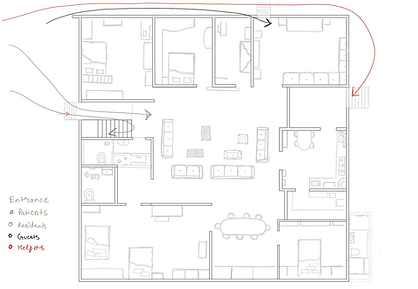

Our house was built in 2011, designed with the clean lines and open-plan logic of modernism. With ten of us living here, six adults and four kids, the architecture has to work hard to keep us from constantly colliding. On paper, the ground floor may be looked at a textbook example of democratic space: a massive central family hall that flows into every other room. But living here for over a decade has taught me that walls are not the only things that divide a home. While the architects might have intended for a more "neutral" space, our family has mapped its own social order onto the tiles. In this house, categories like gender, age, and professional status aren't enforced by doors or spaces, but by "orbits", the specific paths we take and the spots we claim at certain times of the day.

The central hall is the heart of the house, and during the day, it’s exactly what the modernist architects promised: a flexible, shared space where anyone can eat, watch TV, or relax. But this "neutrality" has an expiration time. Every evening, as the elders return from work, a quiet, traditional script takes over. Despite their professional standing, the women in our family usually arrive first to manage the kitchen and meals. The architecture doesn't force this, but it facilitates it. The kitchen, tucked away with its store and washing room, becomes a female-dominated zone of production while the hall remains a male-dominated zone of consumption.

Not like the space forced this gender difference or even rules that were forced onto them, even if the spaces are more male or female dominated, there were no specific restrictions that for entering or helping out in the space, it’s the habit that has been passed down that allows this. There are also some days where the gender roles are reversed when the females sit and in the central hall and eat and males prepare food. Also, the seating in the hall follows a silent hierarchy. My Dada, Papa, and Chacha have specific spots they’ve occupied since 2011. It’s not a rule, but a "spatial anchoring" that turns an open room into a structured one. The women and children move through the space to deliver food or help out, creating a dynamic where the men are the "stationary" centre and everyone else is the "mobile" support.

The image above highlights the movement of my parents moving thorugh and occupying space throughout the day. The way we’ve used the kids' room highlights how age becomes a category of spatial analysis. Originally, that room was meant to be a shared social location for all four children. However, space in a large family is often claimed through a "seniority succession". As the eldest, I moved in first, followed by my siblings and cousins. By the time the youngest arrived, I was a "grown-up" who needed my own space.

Without ever building a physical barrier or making an explicit rule, the room shifted from a communal play area to "my room". This wasn't about exclusion, the others were still free to enter, but about a psychological shift in ownership. It shows that in a modernist house, the "function" of a room isn't what’s on the blueprint; it’s determined by whoever has been there the longest. My presence in that room became a "soft" boundary that the younger kids naturally respected, proving that age can create a private room even when the door is wide open.

One of the most critical aspects of our house is how it handles "outsiders." We have a separate entrance for helpers that leads directly from the lawn to the kitchen. While they can use the main gate, they naturally gravitate toward this service spine. It’s a subtle architectural filter that keeps the "work" of the house separate from the "social" life of the family.

In contrast, the most "public" part of our private life is the staircase. Because my mother’s clinic is on the second floor, the stairs are a thoroughfare for patients. This is where the modernist goal of "utility" creates the most friction. Family members, like my Chacha and Chachi have to share their primary path to their private rooms with strangers. Here, the house stops being a "sanctuary" and becomes a place of work, proving that in a place where most of the elders are doctors, professional identity often trumps domestic privacy.

Despite these roles, the house feels far less segregated than a traditional Indian home because of its visual transparency. In older houses, the kitchen might be a dark, isolated cell, but here, the family can see into the kitchen from the hall. We only hide the work of cooking when guests are over and we move to the formal dining table where the kitchen is shielded to ensure a smooth flow of service.

This creates what I call "hierarchical supervision". Because the hall is a panopticon, a place where you can see almost every door, authority isn't locked in one office. It’s held by whoever is home. If the elders are at their workspaces, the next person in the age hierarchy takes the "watch". The open plan didn’t erase our traditional hierarchy; it just makes it more fluid and efficient.

I would preserve the Central Hall's transparency. While it enforces a hierarchy, it also enforces connection. The "panoptic" nature of the hall,where you can see the kitchen, the stairs, and the entrance is what allows us to function as a unit without being siloed. Removing this would destroy the "hierarchical supervision" that keeps a 10-person house orderly, but I would think of changing the design by replacing fixed seating with modular, lightweight topography. Think of sunken seating pits or tiered wooden platforms with movable cushions. Also, The staircase is currently a site of friction where patients and family members collide. As a designer, I would introduce a secondary, "fast" vertical circulation. A dedicated spiral staircase or a separate entrance for the clinic would restore the main staircase as a private domestic spine, protecting the "sanctuary" of the upper-floor residents from the public gaze of the clinic.

Moving beyond phenomenology, beyond just how I feel in my room, required looking at how the house dictates the lives of all ten of us. Our home is not divided by brick, but it is deeply zoned by habit or as orbits as I termed earlier. The Pooja room belongs to my Dadi because she spends the most time there, just as the central seats belong to the men in the evening. The house is "less divided" only because we have successfully layered our complex family dynamics onto a simple, open grid. The architecture provides the stage, but our age and gender still write the play.